Overlooked, Undervalued: Cornell Research Seeks to Elevate Home Care Workers

Categories

A multidisciplinary team of Cornell researchers is collaborating to elevate the value of home care workers while improving their working conditions and patient outcomes.

By Susan Kelley

“Stop it, stop it!” Yanick Pierre-Louis, 68, slapped her knees, frustrated they wouldn’t stop trembling. Again, her body refused to do what she wanted.

She had just spent an excruciating 25 minutes walking, grimacing with each step, from her recliner in her Brooklyn home to her front door and back, leaning on her walker. Marie Dorvilne, her home care worker since 2017, walked behind Yanick and circled her arms around her torso. She used her knee to help Yanick bend her own.

Besides rheumatoid arthritis in her knees and shoulders, Yanick struggles with gout, diabetes, coronary artery disease, memory issues, headaches, and incontinence. She is a breast cancer survivor.

When they made it back inside, Marie eased Yanick down to the recliner. “I don’t turn my back until I know she is on the chair – sitting, not standing,” says Marie, a certified nursing assistant with 18 years of experience in the profession. “I don’t trust her to stand for one minute.” She elevated Yanick’s feet in a recliner and rubbed Yanick’s knees with swift, gentle strokes, her light blue nails making a circular blur. “You’ll be all right, you’ll be OK,” she says. In a few minutes, Yanick’s knees stopped trembling.

Between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m., Marie is Yanick’s bather, dresser, cook, companion, cheerleader and health care manager. She monitors Yanick’s blood pressure, gives her medications three times a day, times her meals to keep her diabetes in check, schedules and takes her to medical appointments, and alerts doctors and Yanick’s daughter to changes in her health. That’s after an eight-hour night shift, taking care of 12 patients at a nursing home. She has one Saturday off every other week.

“Some people have time to relax, but I don’t have time to relax,” Marie says. “But in a way, I feel like I’m not working. I feel like I’m helping her. I look at it like she’s my mother.”

Marie’s caregiving inspired Yanick’s doctor, Dr. Madeline Sterling ’08, assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, alongside experts from the ILR School and Cornell Tech, to launch an ambitious, multidisciplinary research program aimed at elevating the value of home care workers – which includes home health aides, home attendants and nursing assistants – while improving both their working conditions and their patients’ outcomes. In three years, the team has partnered with the country’s largest health care worker union to produce more than 20 academic papers that aim to reshape the way policymakers view this critical workforce. In June, they began clinical testing of one of their interventions.

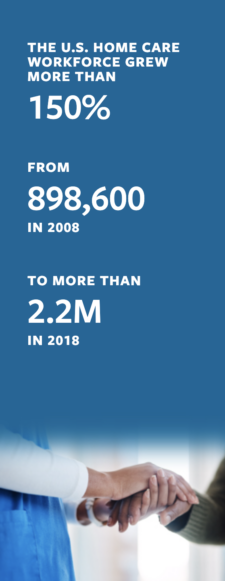

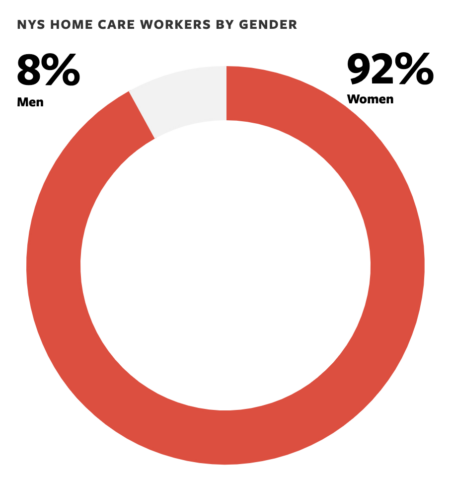

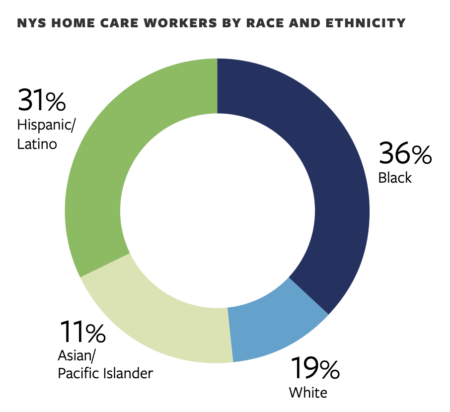

The research illuminates how the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the value of these workers – mostly middle-aged immigrant women of color – while the demand for their services is at a historic high. Yet here in New York state, they are paid on average $15 per hour – about $19,000 per year – and their work is chronically overlooked and undervalued by care teams.

The technology available to them is often out of date and rudimentary – designed mainly to track the workers rather than provide them with tools and support. And though they usually have the most-detailed knowledge of their patients’ conditions, they have almost no interaction with or feedback from their patients’ doctors or specialists.

“Most patients, like Yanick, actually want to be at home, they want to be aging in place,” Sterling says. “It’s a shift that we need to make, to start paying attention to home health providers, who are providing essential day-to-day care to patients to help manage their chronic diseases, and really integrate them into the medical arena.”

Unseen contributions

For Yanick’s first appointment with Sterling, Marie came along.

“Marie slipped into the room, carrying both of their jackets, a bag of medications, hospital discharge papers and a notepad,” Sterling and colleagues wrote in a paper guiding clinicians on how to involve home care workers in their patients’ care. “She hurriedly took out a pen and asked, ‘What did I miss?’”

“What struck me the most was how involved and passionate she was about delivering high-quality care to my patient,” Sterling says. “It was really through interactions in the office where I saw just how much she was observing in the home.”

Marie cooks Yanick three healthful meals per day, makes sure she has eaten before taking her daily 20 pills, and does Yanick’s physical therapy with her.

“She knew when symptoms changed. She also knew when medications were not helping, or when it was time to go seek care,” Sterling says.

That prompted the Cornell team to launch a series of studies defining the unseen contributions of home care workers, establishing evidence of their value and revealing the lack of equity this workforce experiences, Sterling says.

One of their recent studies, which they conducted through Cornell’s Survey Research Institute, suggests home care workers assist with a far wider scope of care than previously documented. Nearly 74% of New Yorkers surveyed said their caregivers provide medical care and/or emotional support. Those patients were twice as likely to view their caregivers as “very important” compared with those who received only personal care.

When Marie sees Yanick become introverted and sad, she takes action. Yanick frequently get depressed by her physical limitations; until about 10 years ago, she lived an active life. She worked in Brooklyn hospitals as a health care worker and raised three children after emigrating from Haiti at age 16.

“I tell her, ‘We don’t have time for depressed. Let’s take a walk outside,’” Marie says. Sometimes she has Yanick sit on the walker and rolls her outside as if she’s in a wheelchair – that always makes Yanick laugh. “That’s what I want to see,” says Marie, 45, who was also born in Haiti and emigrated to the U.S. at age 23.

“She really loves me,” Yanick says. “She’ll say, ‘Come on, smile!’ I feel content with the care. She’s beautiful. She really touched my heart.”

That kind of emotional support has become even more important during the pandemic, when so many vulnerable older people are isolated at home – but it comes at a cost to home care workers. The Cornell team conducted the first study on home care workers’ experiences during the pandemic in the U.S. – and found New York City home care workers faced a higher risk for COVID-19, because many relied on public transportation and frequently lacked protection like masks and gloves. They also faced higher risks to their mental and financial well-being and felt inadequately supported and generally invisible.

The pandemic also exacerbated many of the baseline challenges that home care workers face: low pay, isolation from doctors and other health care providers, physically demanding work, medically challenging patients, unpaid travel time, and frequently changing workplaces that may include unsafe working conditions. “You never know what you’re going to come across. Are you going into a home where there’s hoarding, where there are bedbugs or rodents or crime, broken elevators?” says Faith Wiggins, director of the Home Care Industry Education Fund of the 1199SEIU, the largest health care worker union in the United States, where Marie is a member.

“We really think it’s important to use research to demonstrate the value of the care,” Wiggins says. “With home care, you can’t remote in. You can’t use AI to replace someone assisting you to transfer from your bed into a wheelchair. There will not be a workforce if the wages remain at the bottom, which right now is where they are: minimum wage.”

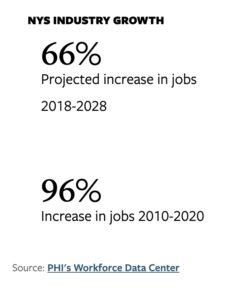

These challenges contribute to a severe shortage of home care workers, while demand from a population that wants to age in place is growing exponentially, says Ariel Avgar, Ph.D. ’08, professor of labor relations, law and history in the ILR School, and an expert in health care labor relations.

“There’s a tendency in the health care industry to view the workforce as a cost – a cost that needs to be minimized,” Avgar says. “In our research we try to demonstrate how this workforce is not just a cost but a central way in which organizations can deliver high-quality care.”

The authors suggest several policies to support home care workers, such as designating them “essential” workers across the U.S., as they are in New York state; legislation to ensure they have masks and gloves; and assigning them to patients on a geographic basis to minimize their need to use public transportation.

“How do we make sure that the knowledge that they have, the insights that they have, make their way into the system in a more robust way?” Avgar says. “It’s happening in some places. But we’re far from where we need to be.”

Real-time assistance

When Marie needs guidance or has a question about Yanick’s care, she’ll try to reach out to various doctors or her home care agency. “Sometimes you call three, four, five times – you get nobody,” she says.

One of the biggest challenges home care workers face is a lack of information about how to handle their patients’ chronic conditions and exacerbated symptoms. The Cornell team is exploring how to use education and technology to address it.

Because the caregivers work in patients’ homes – isolated from doctors, nurses and other home care workers – they can’t learn from others or ask even questions, says Deborah Estrin, the Robert V. Tishman ’37 Professor and associate dean for impact at Cornell Tech, and professor of population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine.

“You don’t have as much chance to see what your colleagues are doing as we do in an office setting or in a hospital setting,” Estrin says.

When home care workers get a new client, they often have no idea what medical conditions they will face. “They often lack the ability to access educational resources on a specific disease that they go into the home with,” Sterling says.

And home care workers want that education.

For example, the team’s research found that when home care workers received training in heart failure – a chronic condition for which they frequently provide care – they had significantly higher job satisfaction compared to those who lacked training.

In June, and as part of Sterling’s Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health, the team began the first clinical trial, in partnership with VNS Health, to test whether training home health aides and integrating them into care teams can improve their experience and patient outcomes. Over the next year, 100 home health aides will take a virtual heart failure training course. Half will be able to message their nurse supervisor at their home care agencies via an app when they have questions. The team believes training and communication will improve patient outcomes, such as avoiding 911 calls and trips to the hospital.

Tech support

When Marie arrives at 8 a.m. each morning, she uses Yanick’s phone to check in with the agency that employs her. “The minute I clock in, they know that I’m here,” she says.

Technology for home care workers is rudimentary; community health workers in Kenya and India use far more sophisticated tech in their work, says Nicola Dell, associate professor of information science at the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute at Cornell Tech and in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science. In the U.S., technology for home care workers is designed primarily to track them, she says. “That certainly has connotations of surveillance and indicates a lack of trust in the workforce, rather than what we would like to see and what we propose: tools that will actually support the delivery of care and support their existing tasks and workflows.”

Dell is principal investigator on a three year, $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation aimed at doing just that. One solution they’ve developed: interactive voice assistants – similar to an “Alexa” or “Siri” device. They presented their findings in early May at the prestigious ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

When a home care worker asks an interactive voice assistant a question, the device answers aloud, so patients and family members know the aide is asking about a medical issue. “It’s providing that information they currently either don’t have or are randomly searching for on the internet, and not necessarily knowing the quality of the information that they’re finding,” Dell says. The device can track completed tasks for the incoming aide, document vital signs, provide information on techniques such as how to assess swelling in a patient’s legs, and suggest when a doctor is necessary.

However, the team’s research also shows the technology comes with complex issues of privacy, power and ethics. “Who gets to turn the device on? Who gets to turn it off, and when? “And whose needs and opinions get prioritized in the process?” Dell says. “That’s why we think it’s important to do the research that we’re doing now and explore these issues before these technologies get deployed at scale and cause all kinds of problems.”

Another idea in the works: replacing telehealth visits with “extended reality.”

“One of the things that we began thinking about is, how can we do even better than just that two-dimensional Zoom-like connection between that remote clinical expert and that local caregiver?” Estrin says. The technology could help with crucial tasks from checking an incision after surgery to helping a patient correctly do rehab after a stroke.

Estrin and her students are experimenting with a headset for home care workers that transmits a real-time video of the patient from different angles to a remote doctor who is also wearing a headset. The doctor sees the video of the patient, while the home care worker sees the clinician’s gestures and directions. “The doctor might say, ‘Place the bandage a little broader’ or ‘Try to support their shoulder differently,’” Estrin says. “That helps the caregiver in the moment.”

She and her team simulate those interactions in their Cornell Tech lab – using a mannequin they named “Dave” after one of the lead graduate students on the project – to create demonstration technologies, get feedback from clinicians and home care workers, and improve the design. The technology could be available in three to four years. “That’s exactly the sort of material that Cornell Tech researchers do so well,” she says. “It’s a wonderful back and forth between the present and the future and back again.”

As a land-grant research university, Cornell plays an important role in developing these experimental systems, Estrin says. The commercial marketplace hasn’t done it, because the complexities of U.S. health care make the business model unclear.

Although technology can play a major role in supporting patients and the people who care for them, it will never replace the human touch, Estrin says.

“We want the last meter of health to be human. I think most of us, that’s what we would choose,” she says. “That’s what excites me about this technology, because it is about bringing superpowers to those caregivers who are touching, listening to and helping patients and really increasing their horizons for the work that they can do.”

What excites Marie is seeing Yanick open a water bottle on her own, or take a step without assistance.

She knows Yanick is happy too when Yanick wants to dance to Haitian compas music – her favorite. “But you know, to stand longer than two minutes, she can’t,” Marie says. “I say, ‘OK, you want to dance? OK, I’m right behind you.’ Just in case.”

This story and video were developed and produced by Noël Heaney and Susan Kelley, with additional support from Matt Fondeur, Sreang Hok, Wendy Kenigsberg, Eduardo Merchán, Marijke van Niekerk and Charles Amyx. It was edited by Lindsay France and Melanie Lefkowitz.